By Dhruv Khullar – July 11, 2017

Growing up, my sister never let our family get a blue “handicapped” placard for the car.

Born three months prematurely with cerebral palsy, she uses forearm crutches to get around. But she’d rather walk half a mile across a mall’s parking lot than take the reserved spot next to the entrance. (I found this particularly exasperating during the holiday season when a ready parking spot is more precious than the presents inside.)

But the prospect of less stigma and greater support for people with disabilities was a central reason my family immigrated to the United States. My sister was born the same year the Americans with Disabilities Act (A.D.A.) was passed — a law that reaffirmed America’s moral and practical commitment to equality.

More than 20 percent of Americans — nearly 57 million people — live with a disability, including 8 percent of children and 10 percent of non-elderly adults. And while the medical profession is devoted to caring for the ill, often it doesn’t do enough to meet the needs of the disabled.

People with disabilities are less likely to receive routine medical care, including cancer screening, flu vaccines and vision and dental exams. They have higher rates of unaddressed cardiovascular risk factors like obesity, smoking and hypertension.

Compared with non-disabled adults on Medicare, disabled people on Medicare are more than twice as likely to forgo care because of the cost, and three times as likely to have difficulty finding a doctor who can accommodate their needs.

The typical response to these types of deficiencies is a call for greater attention to the issue in medical school curriculums. That may be part of the solution. But I’ve sat through enough online modules and uninspired lectures to recognize their limited utility.

Far more powerful for medical trainees and the profession would be having more students, colleagues and mentors with disabilities, who understand how a particular impairment does — or doesn’t — affect daily life.

It’s Not Even the Disability Itself

Often the barrier to medical care isn’t the disability but a health system poorly equipped to handle it: a lack of transportation, accessible medical equipment and safe methods of transfer. These structural problems can be compounded by cultural ones: stigma, communication challenges and inadequate training for clinicians and staff.

In one recent study, researchers called more than 250 specialty practices to make an appointment for a fictional patient they said was partly paralyzed because of a stroke and could not transfer herself from a wheelchair to the exam table. More than 20 percent of offices refused to book an appointment, saying that their building was inaccessible to wheelchairs, they didn’t have height-adjustable exam tables, or their staff wasn’t trained to move the patient. Many practices that did agree to make the appointment admitted they didn’t have the necessary equipment to move the patient, and might need to skip parts of the physical exam.

More worrisome is recent evidence that patients with disabilities don’t always receive the same treatments for the same medical conditions. One study compared breast cancer treatment for women with and without disabilities. Researchers found that women with disabilities were much less likely to undergo breast-conserving surgery than full mastectomy — and those who did receive breast-conserving surgery were less likely to get radiation afterward, which is needed to eradicate residual cancer cells. Over all, they were about 30 percent more likely to die of their cancer.

Disabled individuals are more likely to feel that their doctors don’t listen to them, treat them with respect or explain decisions properly. Doctors often make false assumptions about the personal lives of patients with disabilities. For example, women who have difficulty walking are much less likely to be asked about contraception or receive cervical cancer screening, in part because doctors assume they’re not sexually active. Disabled patients are also about 20 percent less likely to be counseled to stop smoking during their annual checkups.

Doctors With Disabilities Are Changing the Profession

More than 20 percent of the American population lives with a disability, but as few as 2 percent of practicing physicians do — and the vast majority acquire them after completing training. Few people with disabilities are admitted to medical school: Medical students with disabilities also have higher attrition rates than non-disabled students, partly because, despite the A.D.A., they don’t always receive the support they need.

A study published last year examined the “technical standards” — expected cognitive and physical abilities — that medical schools require for admission. (Schools are free to determine these standards as they see fit in accordance with the A.D.A.) Researchers found that while most medical schools had such statements listed on their websites, many statements were difficult to find, and only one-third of schools explicitly said they would support accommodations for disabilities. More than 60 percent lacked information on who would be responsible for providing accommodations, the student or the school.

Increasingly, though, doctors with disabilities are changing the profession. Dr. C. Lee Cohen, a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, has a condition that resulted in partial hearing loss in both ears. She uses an amplified stethoscope to listen to patients’ hearts and lungs, and previously used an FM transmitter device to more clearly hear lectures in school.

“I’m better at communicating with older patients who have hearing loss,” Dr. Cohen said. “From my experience, I know that when you can’t hear well, your brain parses words and syllables in a certain way. Instead of asking people to repeat themselves, I ask them to rephrase themselves. So when my patients are hard of hearing, I know which sounds they’ll have trouble with. I rephrase so they can understand.”

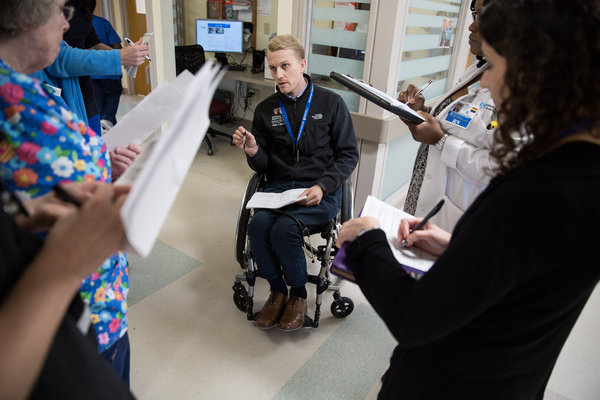

Dr. Gregory Snyder, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, has paralysis in his legs after a spinal cord injury during medical school. He uses a wheelchair and says that he’s sometimes mistaken for a patient while working. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

“It reminds us that at some point we’ll all be patients,” he said. “And perhaps, when we least expect it.”

Over the course of our lives, most of us will acquire a disability: More than two-thirds of Americans over the age of 80 have a motor, sensory or cognitive impairment.

Dr. Snyder remembers the difficulty of adjusting to life as a patient after his accident, and the long road to recovery. But he says his disability and rehabilitation have fundamentally changed the way he cares for patients — for the better.

“I would have been this six-foot-tall, blond-haired, blue-eyed Caucasian doctor standing at the foot of the bed in a white coat,” he said. “Now I’m a guy in a wheelchair sitting right next to my patients. They know I’ve been in that bed just like they have. And I think that means something.”

There’s good reason to believe a more diverse work force — one that includes doctors with disabilities — would be good for patients and doctors. Patients of various backgrounds tend to feel more comfortable with physicians like them, and that’s true for people with disabilities as well.

Having mentors and colleagues with disabilities fosters understanding of different abilities and perspectives, and creates an environment that challenges negative biases about those groups. My sister, as just one example, was the beneficiary of policies (the A.D.A.) and a community that have allowed her to thrive: She recently graduated from medical school and is now training as a radiation oncologist.

Dhruv Khullar, M.D., M.P.P., is a physician at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital and a researcher at the Weill Cornell Department of Healthcare Policy and Research. Follow him on Twitter at: @DhruvKhullar.