By Kyle Spencer – August 3, 2017

Half a dozen students, some in Syracuse University T-shirts, sat around a conference table joking about appropriate job interview outfits. No bathing suits, pajamas or Halloween costumes. Added their instructor, not joking: “No tank tops.”

Then Brianna Shults, leading the workshop with a kindhearted but no-nonsense approach, launched into the Q. and A. section. “So if I identify my interview outfit, should I wear it to bed the night before so I’m all dressed and ready?”

“No!” the group responded in unison.

“And before you put your clothes on, what’s the most important step?”

“Shower!” a few called out.

Ms. Shults, an internship and employment coordinator, closed the conversation with a sartorial tip that experience has taught her needs mentioning: “No dirty clothes!”

Why not? Meghan Muscatello piped in: “Because then you’d be smelly.” The room erupted in laughter. “And if you have a cat or a dog, make sure you leave it hanging so they don’t get it all hairy.”

This might sound like a typical lesson in the age of anything-goes office wear, but these millennials aren’t so typical. Ms. Muscatello and her peers belong to a pioneering group of students with significant intellectual disabilities who are enrolled in Syracuse’s InclusiveU.

The students — about 60 are expected this fall — have various degrees of disability, often with related developmental disorders. One communicates through a picture board and an iPad; a helper supports her arm as she taps out words. Another, a movie buff who wrote a play for his theater class, has Asperger’s syndrome. A sports enthusiast who interned this past spring with the Syracuse Orange men’s basketball team has Down syndrome.

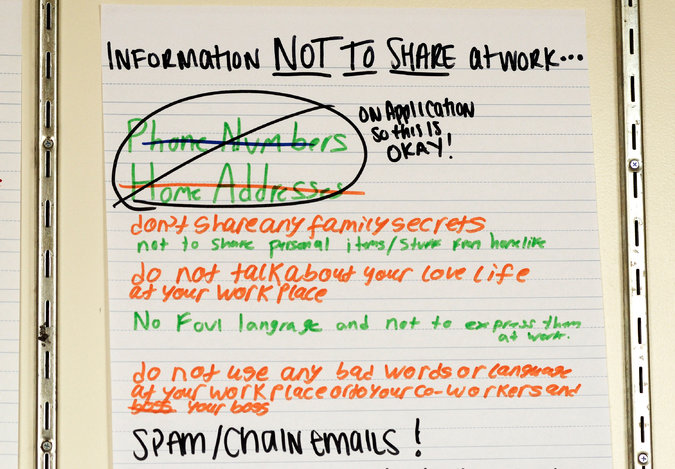

During the first three years, the students choose “majors” and audit five to six college classes that align with their interests. They complete homework and take tests, ungraded, with the help of note takers, who are supplied by the university to sit with them in class. Popular majors: disability studies, sport management and food studies. Favorite classes: first aid, “Animals and Society” and “Peoples and Cultures of the World.” The students also take a spattering of electives, like hip-hop dance, jewelry-making and photography. For their fourth year, they intern on campus. All the while, they attend workshops — on email etiquette, workplace chitchat and résumé writing — and spend time with student volunteers at trampoline parks, basketball games and pizza parlors. The goal: to become employable.

Fifty years ago, young people with intellectual disabilities were often institutionalized or kept home, out of the public eye. Thanks to 1975 legislation now called the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, more than 90 percent of them now go to public schools with mainstream students.

And that, experts say, has altered expectations around what they ought to achieve.

Brian Skotko, the co-director of the Down syndrome program at Massachusetts General Hospital, sees 250 patients with the condition a year. He makes this observation: “Parents with newborn babies now want to know, ‘What are the possibilities for school? What are the college and independent living opportunities?’ ”

The hope for their children is that they can learn to shoulder jobs and live quality lives.

Today, there are some 265 work-readiness college programs for students like the ones at InclusiveU, according to Think College, a federally funded coordinating center at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. That’s a big leap from 2004, when there were just 25. Unlike programs for high-functioning students on the autism spectrum, these award certificates, not degrees.

What the students want upon graduation are good jobs, not short-term gigs restocking shelves or handing out fliers on street corners but employment that relates to their interests and plays to their strengths. Therapists, economists and philosophers have long equated happy, fulfilling lives with meaningful work, no matter one’s intellectual ability.

Some research indicates that college helps. A 2015 survey by Think College of some 900 intellectually disabled students found that those who spent most of their time in traditional classes, soaking up campus culture and fine-tuning their social skills, had better job rates than those who spent most of their time in specialized classes. The length of time a student spent in a program also increased their chances of employment.

But the same survey found that only 40 percent of students exiting programs in 2015 were in paid jobs within 90 days of leaving. That’s a lot better than the 7 percent employment rate for similarly disabled adults within the general population, as reported in a 2011 study. But it’s still a dispiriting number.

Syracuse University, which has offered a loosely monitored class-auditing program since 2009, has struggled to get its students paid positions. It has not tracked employment, but informal interviews with 30 certificate recipients indicated that only about a third were employed for at least two days a week this past spring, making at least a minimum wage. One graduate had landed a position in the campus parking permit office after an internship there. Not so lucky was a 2012 graduate who got a job wearing a billboard sign outside a pizza chain. He promptly quit. Another did volunteer work checking patients in at a hospice.

To improve outcomes, the university overhauled the program in 2014, rebranding it as InclusiveU. And with a $2 million federal grant, Ms. Shults was hired to design the internship year and workshop curriculum, which replaced a fourth year that had been purely academic. The first class will graduate in 2019, but already Cate Weir, Think College’s program director, cites InclusiveU as a model.

Syracuse has a longstanding reputation for commitment to disability advocacy, starting in 1946 when it opened a special education research department and began attracting top talent in the field. In recent years, the university has done high-profile work in communication methods for individuals with disabilities, and now has 10 disability-related centers. One is the Lawrence B. Taishoff Center for Inclusive Higher Education, which houses InclusiveU.

Beth A. Myers, the director of the Taishoff Center, said that students in the newly revised program begin brainstorming their career plans when they arrive as freshmen, and are guided to think deeply about their interests, their strengths and their weaknesses.

The challenge is striking an honest balance between being too optimistic and not stretching them enough. “Low expectations is a serious issue with this population,” said Bud Buckhout, who oversees the program. “But you don’t want to overwhelm people, either.”

For some, striking that balance has led to disappointment. Bob Pangborn, a 22-year-old dramaturge with autism, spent his teens performing in community theater. At Syracuse he learned that acting was an unreliable profession. He was encouraged to consider something more practical, like ushering at a movie theater.

The conversations led Kaitlyn O’Reilly, who was born with a rare chromosome abnormality, to take a disability studies class popular among sociology majors. Her end-of-semester assignment was an evaluation of campus crosswalks unfriendly to visually impaired students. She and her note taker had created a map showing where to put raised street markings and audio boxes.

The room was silent as Ms. O’Reilly, who has a speech impairment that can make it difficult to understand her, stood next to a podium and went through the locations on the map, displayed on a whiteboard.

“These ones are good, these ones are bad and these ones are half not O.K., half good,” she said, pointing at green, yellow and red dots on the map — a color-coded grading scale.

After her presentation, her professor wondered if crosswalks deep inside the campus were more problematic than ones in areas popular with visitors. Ms. O’Reilly said yes. Then a student told the class that she herself had noticed how unsafe one of the crosswalks Ms. O’Reilly had mentioned was, even for students who are not impaired. Ms. O’Reilly nodded knowingly. “Yeah, you don’t know where you can walk across the street.”

Ms. O’Reilly, who is in her first year in the program, said the presentation had given her a sense of her own power. “I felt very proud of myself,” she told me. Ms. Shults sees her getting an internship at one of the campus’s disability centers. Ms. O’Reilly says she thinks she’d like to work with children.

Ms. Muscatello, who at 28 is in her final year, knows exactly what kind of career she wants. She envisions herself in an office wearing nice clothes, answering phones, filing papers and having lunch with colleagues.

InclusiveU helped her develop that vision.

With an I.Q. around 65, she finds simple things like work manuals and basic textbooks challenging. Big words confuse her, and her math skills don’t go past third grade. But she is funny and warm, with an easy smile. She likes Harry Potter books, natural disaster movies and her cat. And “I love it here,” she said of the campus.

Ms. Muscatello spent her teens in a special program in high school and then entered a life skills program for students with intellectual disabilities. On completion, she landed a job at a Price Chopper, stocking shelves. At first, she liked unloading jars of applesauce and cans of tomato soup. But eventually the work felt demeaning.

When mayonnaise jars broke or one-pound bags of flour cracked open, it was Ms. Muscatello who was asked to do the cleanup. “I’d go home all covered in flour,” she said. “You could stick me in the oven and bake me like a cake.” She would cut her hands when cleaning up glass. Her mother, a labor and delivery nurse, wanted more-challenging work for her daughter and more respect. “I wanted more of a people job for her.” Ms. Muscatello did, too.

This past year, she participated in three campus internships. In the fall, she interned in the repair shop. The first few days, the program’s job coach shadowed her as she learned how to fill out work order forms when complaints came in that light switches or elevators weren’t working. Once on her own, Ms. Muscatello found the work manageable but boring. For her second job, she worked in the day care center reading to preschoolers, helping them with yoga poses and, once, calming them when a raccoon got stuck in the playground. But she found the work exhausting.

She found her sweet spot in her third internship, working as an assistant in the quiet, carpeted offices of the Institute for Veterans and Military Families. The hope was that maybe she could stay on after the internship.

I first met Ms. Muscatello in the office break room at the institute. She was learning how to deliver mail and deal with the stubborn paper shredder, and trying to remember who was whose assistant.

When an officemate teased her that the boxes she was delivering might be too heavy for her, she insisted: “I’m capable of carrying some of the heavy boxes.” She does not want to be underestimated.

One spring morning on the North Shore of Long Island, dozens of eager parents, some from as far away as Illinois, meandered around the tree-lined campus of New York Institute of Technology, which houses the Vocational Independence Program, a three-year residential program with about 45 students. Staff members stood behind folding tables inside a sprawling lobby to hand out glossy promotional material, while parents nibbled on muffins and bagels. More than 1,000 students have enrolled since its inception in 1987.

Once the group had settled in the auditorium, Paul Cavanagh, the senior director, told parents about the 3:1 student-to-staff ratio, the extensive job training (traditional college classes, internships at nearby hotels and restaurants) and life skills classes (banking, budgeting, cooking, apartment living). But the school has not kept records of postgraduate employment.

Parents took notes. During the questions segment, one parent wanted to know whether there were enough athletic activities. (Yes, baseball and volleyball games are organized by the students.) Was there an I.Q. cutoff? (No.) What is the screen-time policy? (Students manage their own screen use.)

Touring classrooms, computer labs and a coffee house where students hold meetings, talent nights and parties, parents talked about their dreams and concerns. A New Jersey mother of an 18-year-old with a developmental disability thought the time away from home would be good. “For him, not me,” she said woefully.

Many of the parents said they were looking for something new for their sons or daughters: an environment where not everybody catered to their every whim, where they were allowed to stumble a bit and take some risks, which they hoped would allow them to build the kind of resilience necessary for independent lives and fulfilling jobs.

New York Institute of Technology has the priciest of the programs, at $50,730 in tuition a year (plus $12,220 for room and board). The Syracuse program averages around $23,200, depending on what classes a student takes. (It will host its first boarder this fall.) Both fees include the cost of mentors and note takers. Nationally, the average cost without support staff, according to Think College, is $11,000.

Such revenue contributes to the proliferation of work-readiness programs. The growth is also a result of a 2008 rewrite of the Higher Education Opportunity Act, which led to the establishment of Think College. It allowed these students, many without a high school diploma or comparable, to use federal financial aid for the first time if they attend an approved program. Syracuse expects to be able to award financial aid by this fall. (Students in some states can use a special Medicaid fund to pay their expenses. School districts — required by law to support educational opportunities for disabled students until age 21 — also help foot some of the bills.)

Some take issue with the programs for supporting what they consider an impractical but prevalent idea — that everyone should go to college — and giving students a false sense of academic accomplishment while costing taxpayers and parents. Instead, they believe these students ought to be funneled into more cost-effective and targeted vocational training programs and apprenticeships.

“If we are going to really help people with significant disabilities, it’s not by pretending they can go to college and do college work,” said James M. Kauffman, a professor emeritus of education at the University of Virginia who has written extensively on special education.

Ms. Weir of Think College says such thinking too narrowly defines how a college education benefits students, ignoring much of the socio-emotional learning that happens for those in their late teens and 20s — with disabilities and without — while clocking time on a campus. Further, she says, just because students don’t get 100 percent of what is taught in a class does not mean they haven’t benefited.

“This isn’t for everybody,” Ms. Weir said. “But it should be a choice. Students with disabilities shouldn’t be told, ‘You can’t have a choice other people have.’ ”

But even as she stridently supports the existence of the programs, Ms. Weir concedes that there are serious challenges. Programs are not accredited, leaving many families more or less in the dark about their quality. For the past few years, a 15-person task force organized by Think College has worked to develop a set of accreditation standards. The report was delivered to Congress last year. Ms. Weir says the next step is to persuade colleges to agree to an accreditation process.

Advocates say that the biggest issue isn’t so much with the programs as with the work force. Many employers worry about the expense and training required when hiring someone with a disability. And low-skilled jobs that might have once been appropriate for this population are disappearing in our increasingly tech-centered economy.

Jonathan Lucus, managing director of the Arc, a job-training service that connects companies with applicants who have intellectual and developmental disabilities, says college programs need to do intense outreach with local businesses. “You’ve got to constantly go out there,” he said, “and shake hands and greet people and kiss babies and talk to these employers and say: ‘Look what we are doing. How can we work together?’ ”

Ms. Muscatello’s journey illustrates how hard that can be.

When I went to visit her a second time at her internship, she was sitting quietly behind the front desk dressed in black slacks and golf shirt. She had a laminated cheat sheet on the desk by her side that her job coach, Angela McPheeters, had made for her. It had all the staff names, their job titles and their extensions in large print.

An administrative assistant sat by her side, giving her the day’s assignment: to empty black binders that had been used for a recent conference, remove the tabs, and place them in a box on the floor. Ms. Muscatello also worked the phones. But when she picked up a call for someone in the entrepreneurship office, she got confused and couldn’t say the word. Another time, pressing the buttons gave her trouble. Her supervisor had told her that if she got better with the phones, there was a good chance they’d hire her.

When Ms. McPheeters got wind of this, she sent Ms. Muscatello home to practice with a photocopy of a telephone with the numbers pad on it and her cheat sheet. She spent days on it, after work and on weekends, announcing: “Hi, I.V.M.F. This is Meghan. Can I help you?” She tapped on the paper numbers with her index finger, as if she were transferring the calls.

But when the semester ended, the supervisor said that funding had been cut and they were not going to be able to hire Ms. Muscatello. “I was a little bit disappointed,” she told me.

A few weeks later, in a cap-and-gown ceremony at a chapel on the main quad, this year’s graduates received their certificates. One now has a job doing clerical work in a municipal office. Another has a position as a shop technician at a carpet cleaning company.

As for Ms. Muscatello, she spent weeks eagerly waiting, her résumé, letter of recommendation and interview outfits, free of cat hair, ready to go. Then one morning she was called in for an interview — and aced it. This month she is expected to begin working the front desk at a YMCA. She got her dream job.

Correction: August 3, 2017

An earlier version of this article referred imprecisely to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. In 1975 the legislation was called the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, and was renamed IDEA in 1990.