There’s something undeniably special in the way Meera Phillips looks at you when you speak. It’s as if your words are the only words that will ever matter, whether you’re talking about something silly or something serious.

The 15-year-old knows the value of hearing what people say. That’s because she’s used to not being heard.

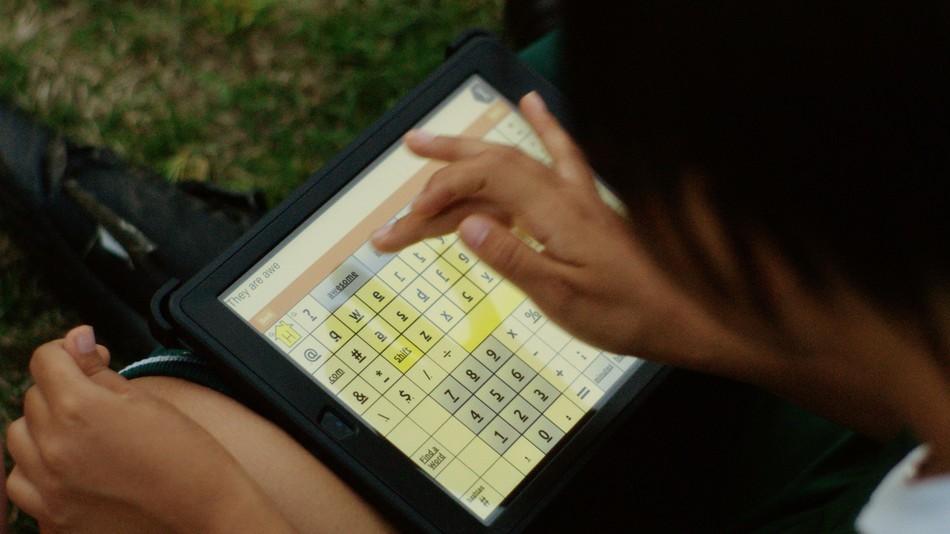

Meera is nonverbal, living with a rare condition called schizencephaly that impacts her ability to speak. But with the help of her iPad and text-to-speech technology, she can make her thoughts and opinions known — and she sure does. From her love of Katy Perry to her passion for soccer, Meera will let you know exactly what’s on her mind. All it takes is a few taps of her tablet, and with a specialized app stringing letters into words, and words into phrases, her thoughts are played out loud.

Meera’s relationship with tech is just one of seven stories featured in a powerful video series created by Apple to spotlight the company’s dedication to accessible technology. The videos were released in celebration of Global Accessibility Awareness Day on May 18, a day emphasizing the importance of accessible tech and design.

“We see accessibility as a basic human right,” says Sarah Herrlinger, senior manager for global accessibility policy and initiatives at Apple. “We want more and more people out there to not only see the work we’re doing, but realize the importance of accessibility in general.”

The videos showcase users with a wide range of disability identities and experiences — from Carlos Vasquez, a blind metal drummer, to Shane Rakowski, a music teacher with hearing loss.

“Now people know I have a lot to say. They know I am smart. They know me. They see me now as Meera.”

And then there’s spunky Meera, who likes to gossip and giggle with her friends on the side of the soccer field and mostly uses her iPad and a text-to-speech app to do so. Her natural voice can only force out short words like “no” and “yes.” While Meera knows sign language, the majority of her friends don’t.

Though she now has tech that works for her, it took Meera a long time to find a way to express herself. In fact, until 10 years ago, getting access to any assistive technology wasn’t even possible.

Meera was born in India, living on the streets of New Delhi until she was adopted by her moms at age 5. She was nonverbal and homeless from birth, meaning she had no education and few ways of communicating.

But through accessible technology, along with education and sign-language learning, Meera has gained multiple ways to communicate.

“Now people know I have a lot to say,” says Meera, who now lives in Atlanta with her moms and younger brother, Tucker. “They know I am smart. They know me. They see me now as Meera — their friend, their student, their neighbor. They know I have opinions and good ideas.”

Accessibility features come standard with each Apple product, meeting a user’s needs right out of the box. That’s unparalleled in the mainstream tech industry, making the company a favorite of people with disabilities.

“There’s not just one feature that encompasses ‘accessibility,'” Herrlinger says. “There’s really a depth and breadth to what ‘accessibility’ means.”

When I ask Meera via video chat how it feels to be able to communicate through her iPad, she taps out an answer on her tablet’s keyboard, letter by letter. When she’s finished, she plays it through a robotic voice: “It makes me feel happy and smart.”

“There’s really a depth and breadth to what ‘accessibility’ means.”

“You are smart,” says Meera’s mother, Carolyn Phillips, after hearing her answer. And she is.

Once, for example, Carolyn entered the house to hear the family’s Amazon Echo inexplicably blaring Taylor Swift’s newest album. Carolyn knew Meera, the only person home at the time, couldn’t speak to the Echo to activate Alexa. Convinced the speaker was on the fritz, Carolyn turned off Taylor’s tunes.

But a couple of minutes later, Swift’s songs were booming yet again. Carolyn then realized Meera had hacked the system, connecting the Echo to her iPad to have it follow her commands. By making the two pieces of tech “talk” to each other, she could play Taylor Swift at top volume whenever she wanted.

The features built into each Apple device, Herrlinger says, allow people with disabilities to customize their devices to suit their own needs — even if one of those needs is blasting “Blank Space.”

Middle school music teacher Shane Rakowski, for example, uses her iPhone to control her hearing aids, with the ability to toggle between a standard mode and a music mode. The music mode helps amplify low notes Rakowski can’t hear otherwise, while the standard mode helps her to instruct her students.

Rakowski discovered her hearing loss four years ago while teaching a music class in Williamsburg, Virginia. One of her students was hitting the low notes on a marimba — but Rakowski didn’t hear any sound.

Suddenly, things started to click. It had always been hard for her to understand the low voices of men, and she always spoke with a loud voice, even in one-on-one conversations. Now these low notes — notes her students could hear clearly — registered only as silence.

“The kids call them my bionic ears. They say I can hear everything now.”

Rakowski, whose musical passion and profession rely on the ability to hear, started using hearing aids a little over a year ago. She switched to an iPhone from another phone company because of Apple’s accessible technology.

“There’s definitely a difference in the way I’m teaching after getting hearing aids,” she says. “The students say I’m not as loud as I used to be. I can hear a student’s question without asking the whole class to quiet down. I can hear kids talking in the back of the classroom, doing things they aren’t quiet supposed to be doing.

“The kids call them my bionic ears. They say I can hear everything now.”

Carlos Vasquez, a blind metal drummer and professional gamer from Houston, Texas, needs something incredibly different from technology than Rakowski. Yet, he uses the same products she does; he just tailors them differently to fit his needs.

“A lot of times when people think of accessibility, they think things need to be ‘dumbed down.’ That’s not true.”

While Rakowski relies on visuals to control the volume of sounds coming through her hearing aids, Vasquez relies completely on sound to navigate his Apple devices. His device speaks aloud what would normally be seen, with Vasquez using taps of his finger and his voice to select options and perform tasks.

“You basically have this device that, out of the box, is accessible to someone who is blind,” he says. “You turn on this feature, and you can use it like anyone else. A lot of times when people think of accessibility, they think things need to be ‘dumbed down.’ That’s not true. It’s just a different way of doing the same thing.”

Vasquez was born with cataracts, which were partially removed when he was very young. After the surgery, he had crystal clear, 20/20 vision. But the cataracts weren’t removed completely, and before his teens, Vasquez developed glaucoma.

At 10, his vision started to fade. By 28, he was completely blind.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EHAO_kj0qcA

Now, Vasquez says he’s adapted to blindness with the help of tech, using his iPhone to assist him in everyday tasks, like making phone calls or using social media.

“With over a billion people on the planet with a disability, that’s a billion reasons for accessible design.”

“Technology doesn’t change your life,” he says. “What changes your life are the things you do for yourself — and then technology can come in and enhance what you are already doing.”

For Vasquez, that means using tech to assist him in handling social media and public relations for his metal band, Distartica. By using VoiceOver, one of Apple’s most well-known accessibility features, Vasquez has access to the same functions as a sighted person.

Apple says this universal, customizable accessibility is the driving force behind its innovations for people with disabilities.

“With over a billion people on the planet with a disability,” Herrlinger says, “that’s a billion reasons for accessible design.”

When I ask Meera if she has anything else to add before we stop video chatting, she keeps coming up with something else to say. She’s a true chatterbox — a captivating teen with stories to tell. But sometimes, even with accessible tech, it still isn’t easy to be heard.

Typing your thoughts letter by letter, even with the aid of text prediction, is tedious work. It allows Meera to be deliberate with her thoughts, but also causes people who are used to quick conversations to lose interest. Meera often struggles to hook people in, failing to keep them around long enough for a discussion.

“Before I had the iPhone and iPad, people treated me like I had a disability. They talked about me, not to me.”

To prevent this, Meera has pre-written statements plugged into her speech-to-text app to help her introduce herself. She plays some for me with the simple tap of a button. One describes her harrowing time as a toddler on the streets of New Delhi. Another explains all the things she likes to do, like playing soccer and listening to music, in hopes of finding friends with common interests.

The tactic isn’t flawless, however. People of all ages still walk away from Meera out of impatience or frustration. But even though Meera has to type out every letter, word, and phrase, she says being able to assert her voice is worth it.

“Before I had the iPhone and iPad, people treated me like I had a disability,” Meera says. “They talked about me, not to me. They didn’t really know me.”

She smiles. It’s the type of grin that travels up to her eyes, leaving them gleaming.

“Now,” she adds, “I can tell them who I really am.”